Generating 2D Fingerprints to Predict Properties of Metal Organic Frameworks Using Machine Learning

With the increase in global transportation and shipping, the need for efficient and safe gas transportation is more important than ever. One method of accomplishing this is through metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). MOFs are a class of crystalline materials with extremely high porosity, inner surface area, and flexibility in network topologies. MOFs are composed of positively charged metal ions connected by organic linkers. This unique composition gives MOFs an incredibly large inner surface area ideal for storing or separating gases.

Currently there are more than 90,000 different types of MOFs that scientists have synthesized. The problem is that trying to create new MOFs from scratch is time consuming and expensive. The physical process involves chemists combining many different chemicals in a beaker and letting the mixture crystalize for several hours or sometimes even days. At the end of this process if they’re lucky, they’ll have a new MOF; otherwise, they’ll need to restart the whole process. By using machine learning to generate likely properties of MOFs based on the MOFs currently in existence, scientists can get a head start on synthesizing new ones.

One aspect of this machine learning approach is trying to predict geometric properties of MOFs such as pore-limiting diameter and largest cavity diameter. Current calculations are done using Monte Carlo simulations which are time consuming and costly. The ability to have a trained model that can quickly verify if a MOF structure is geometrically similar to those that already exist would be advantageous.

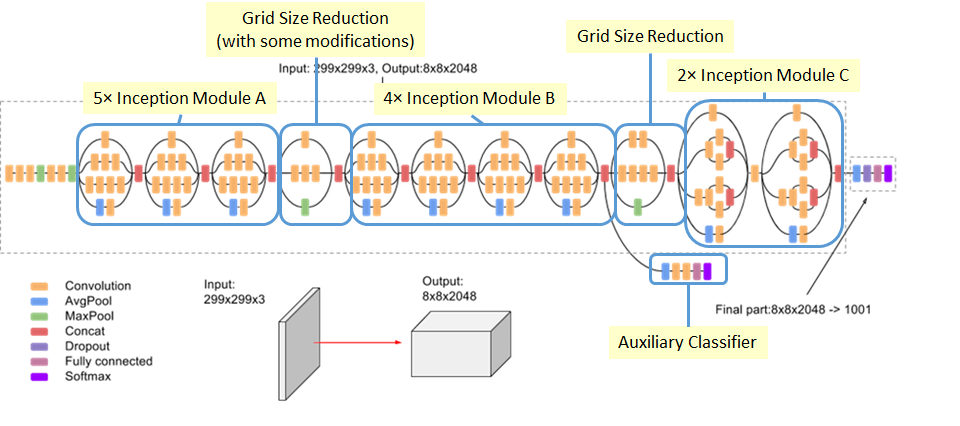

Our team at Binghamton University (Shehtab Zaman, Kenneth Chiu, Michael J. Lawler and myself) undertook the task of developing this model. We decided to use a 2-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). More precisely the InceptionV3 architecture with transfer learning activated as seen in Fig. 1. We decided on this model because of its pre-trained nature and high-performance on ImageNet, a dataset of 1 million labeled images. The problem is that MOF coordinates are in 3-dimensional space so in order to utilize a 2D CNN we need a dimensionality reduction algorithm which can preserve the geometric properties that are represented in the 3D space.

We did also attempt using a 3D-CNN, but because a substantial quantity of MOFs had atom counts in the thousands, a 3D-CNN would be largely inefficient. We also hoped to utilize the pre-trained latent space of the InceptionV3 architecture which excels at recognizing tiny differences in edges and features of the images.

Fig. 1 InceptionV3 Architecture. For transfer learning only the final part of the model is trained on the new data.

To solve this issue we applied multidimensional scaling (MDS) to the 3D coordinates. This resulted in a 2D matrix of the atom positions which hopefully preserves the geometric properties of the original 3D MOF. While some information is definitely lost from the 3D to 2D reduction, our hope is that it is small enough to not affect our predictions. The formula for classical MDS is as follows:

\begin{equation} \label{mds} StressD(x_1,x_2,…,x_N) = \left(\sum{x \neq j=1,…,N}(d_{ij}-||x_i-x_j||)^2\right)^{1/2} \end{equation}

Where:

\begin{equation} \label{d} d{ij} = \sqrt{\sum^p{k=1}\left(x{ij}-x{jk}\right)^2} \end{equation}

And X is a configuration of points in low dimensional space p. D is a distance matrix that approximates the interpoint distances of X, and StressD is a residual sum of squares.

We also tested MDS against other dimensional reduction methods, but we ultimately decided MDS was the best based on our testing with synthetic 3D spheres. Below is a figure of MDS on a 3D MOF sample:

We used the CoRE MOF 2019 dataset with expanded geometric properties such as henry’s constant, and surface area for our testing. The dataset contains over 14,000 MOF samples which also makes transfer learning the preferred approach since it excels at problems with low training samples. We used a few different methods of parsing the MOFs with varied results.

The first method was just passing in the direct MOF coordinates (right). This resulted in low prediction accuracy so we instead passed in the MOF with coordinates outside the unit cell concatenated on as well (middle). This had better results, but still not enough to make the model plausible. The last method we tried was passing in the distance matrix of the MOF to MDS (left). This had the best results with an average error of 85% and a median of 45%, but with an error that high we could not publish the results in an academic conference.

We still felt like our work was worthwhile so we decided to showcase it in this report so that other researchers might be able to discover a new approach to our methods. Some potential ideas that we thought of, but did not pursue, were to use a 2D image of the full 3D MOF from different points of view with partial alpha values to hopefully represent areas of low density atom concentrations that the model could recognize. If any interested researchers would like to build off our work, it is available at: https://github.com/szaman19/Materials-Search.

Acknowledgments

This material is based on work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant No. OAC-1940243.

Bibliography

Papers with code—Inception-v3 explained. (n.d.). Retrieved March 24, 2022, from https://paperswithcode.com/method/inception-v3

Berger, M. (n.d.). MOF Metal Organic Framework—Definition, fabrication and use. Nanowerk. Retrieved March 24, 2022, from https://www.nanowerk.com/mof-metal-organic-framework.php

Han, Y., Yang, H., & Guo, X. (2020). Synthesis Methods and Crystallization of MOFs. In (Ed.), Synthesis Methods and Crystallization. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.90435

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: